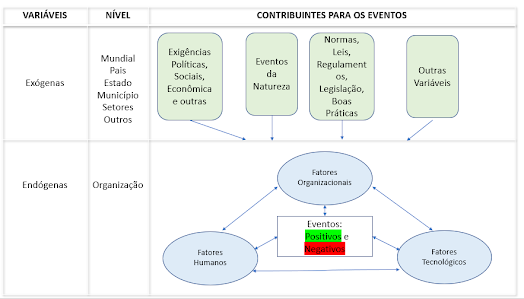

Prevent Tragedies - Challenger - Date Actions and RISK MANAGEMENT modules, AND THE PROACTIVE SAFETY METHOD, RISKS AND EMERGENCIES

Figure - Challenger Explosion

Challenger - Date Actions and latent failures

Reference:

James Reason – Human Error

1977 - During test firings of the solid–rocket booster, Thiokol engineers discover that casing joints expanded (instead of tightening as designed). Thiokol persuades NASA that this is “not desirable but acceptable.” It was also discovered that one of the two O – ring joint seals frequently became unseated, thus failing to provide the back – up for which it was designed.

1981 - NASA plans two lightweight versions of the boosters to increase payload. One is to be of steel, the other made of carbon filament. Hercules submits an improved design for the latter, incorporating a lip at the joint to prevent the O – ring from unseating (termed a “capture feature”). Thiokol continues to use unmodified joints for its steel boosters.

November 1981 - Erosion (or “scorching”) was noticed on one of the six primary O – rings. This was the same joint that was later involved in the Challenger disaster.

December 1982- As a result, NASA upgrades the criticality ratings on the joints to 1, meaning that the failure of this component could cause the loss of both crew and spacecraft.

April 1983 - Some NASA engineers seek to adapt the Hercules “capture feature” into the new thinner boosters. The proposal is shelved and the old joints continue to fly.

February 1984 - Just before the 10th shuttle launch, high–pressure air tests are carried out on the booster joints. On return, an inch–long “scorch” was found on one of the primary O – rings. Despite the “critical – 1” rating, Marshall Space Center reports that no remedial action is required. No connection was noticed between high–pressure testing and “scorching”, although pinholes in the insulating putty were observed.

April 1984 - On the 11th flight, one of the primary O – rings is found to be breached altogether. This was still regarded as acceptable. No connection was made between high–pressure air testing and scorching, even though the latter was found on 10 of the subsequent 14 shuttle flights.

January 1985 - Breaches (“blowbys”) are found on four of the booster joints. The weather at launch was coldest to date: 51 degrees F with 53 degrees wa F at the joints themselves. No connection noted.

April 1985 - On the 17th shuttle mission, the primary O – ring in the nozzle joint fails to seal. Scorching found all the way round the joint.

July 1985 - After another flight with three blowbys, the NASA booster project manager places a launch constraint on the entire shuttle system. This means that no launch can take place if there are any worries about a Criticality – 1 item. But waivers may be granted if it is thought that the problem will not occur in flight. Waivers are granted thereafter. Since top NASA management was unaware of the constraint, the waivers are not queried.

July 1985 - Marshall and Thiokol engineers order 72 of the new steel casing segments with the capture features.

July 1985 - Thiokol engineer writes memo warning of catastrophe if a blowout should occur in a field joint.

August 1985 - Marshall and Thiokol engineers meet in Washington to discuss blowbys. Senior NASA manager misses meeting Subsequently, 43 joint improvements were ordered.

December 1985 - The director of the solid rocket motor project at Thiokol urges “close out” on the O – ring problem (i.e., it should be ignored) because new designs were on their way, and the difficulties were being worked on. But these solutions would not be ready for some time.

January 23, 1986 - Five days before the accident, the entry “Problem is considered closed” is placed in a NASA document called the Marshall Problem Reports.

January 27, 1986 - It is thought probable that, on the night before the launch, the temperature would fall into the twenties, some 15 degrees F colder than the previous coldest launch a year earlier. (The actual launch temperature was 36 degrees F, having risen from 24 degrees F.) At this point, Allan McDonald, Thiokol’s chief engineer at the Kennedy Space Center (the “close out” man) experiences a change of heart and attempts to stop the launch.

January 28, 1986 - The Challenger shuttle is launched and exploded seconds after, killing all seven crew members. A blowout occurred on one of the primary booster O – rings.

Comentários

Postar um comentário