Prevent Tragedies - Lessons learned from the Three Mile Island (TMI) accident and RISK MANAGEMENT modules, AND THE PROACTIVE SAFETY METHOD, RISKS AND EMERGENCIES

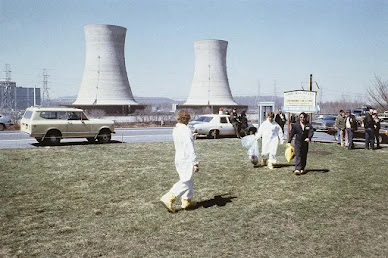

Figure - TMI accident

Lessons learned from the TMI accident

Reference: Human and organizational factors in European nuclear safety: A fifty-year perspective on insights, implementations, and ways forward

The period before the TMI accident was characterized by a building spree, where several new NPPs were put into operation each year. That rapid rate of the building also occurred in Europe, with new plants in Belgium, Germany, Finland, France, Holland, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. In the US market, four large companies—Babcock & Wilcox, Combustion Engineering, General Electric, and Westinghouse— competed fiercely. Of these, Westinghouse won contracts in Europe. The owners of the new plants in the US were mostly companies with experience from coal-fired power plants, which—according to some analysts—conceived nuclear power as “a way of boiling water to get steam to turn a turbine”. Consequently, that conception did not place much emphasis on HOF issues, besides how humans had to operate machines, and their malfunctions. In Europe, the new plants were commonly national undertakings, requiring investment in research and education. The new plants in the US often recruited personnel from nuclear submarines for their operations, resulting in plant cultures in the US and Europe diverging to some extent regarding technical and, in particular, HOF issues [8].

Two units were built at Three Mile Island near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. On 29 March 1979, the TMI-1 had already operated for nearly 4 years and was down for refueling. TMI-2, a sister plant to TMI-1, had entered commercial operation only three months before the accident. A small disturbance (i.e., a postulated initiating event, PIE) at TMI-2 on the secondary side increased reactor pressure and led to the opening of the pressure-relief valve. The accident sequence started when the valve did not close as it was supposed to. The operators did not notice the open valve and large amounts of reactor coolant escaped. The operators could have stopped the sequence of events before its development into an accident, but deficiencies in several systemic HOF issues gradually led to the unfolding accident.

The sequence of events has been thoroughly analyzed, not only in official documents [9,10] but also in reports from nuclear institutions [11] and in many academic articles [12]. The verdict is unanimous: the accident was caused by many simultaneous deficiencies regarding control room designs, training, operating procedures, and application lessons learned [9]. In addition, investigations revealed problems with systems that manufactured, operated, and regulated nuclear power production including structural problems in the organization, process failures, and lack of communication between key individuals and groups [13]. These findings immediately led to much activity in the nuclear industries around the world, in the national regulatory agencies, and in the global research community. We do not want to sum up the massive responses to the accident around the world, but we still want to pick a few to illustrate the level of concern this nuclear accident introduced in various places:

- In the US, the accident led to the establishment of the Institute of Nuclear Power Operation (INPO), which can be seen as an institution located between the industry and the regulator. INPO got an important role in developing organizational approaches to safety within the nuclear industry in the US [14].

- The United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission (USNRC) issued many NUREG documents (i.e., regulatory documents by the US regulator USNRC), which were intended to take care of the problems.

Two documents (NUREG-0700; NUREG-0800) are still relevant and are kept updated even today [15,16].

- In Sweden, the accident led to a referendum considering the Swedish nuclear power program. Three possibilities were put on the vote and all assumed a stop to building new NPPs and plans for shutting down the 12 reactors that were operating at that time.

In retrospect, the TMI accident is astonishing because most of the recommendations that were suggested after the accident were not new.

There should have been common knowledge and experience to avoid the most obvious problems that were subsequently highlighted. A remarkably similar sequence of events, for example, had taken place in an incident at the Davis-Besse NPP in 1977 but the TMI operators had not been informed or given training about it [9]. Another example is the NATO conference held in Berchtesgaden, Germany [17], where a presentation went through the findings of a forthcoming report [18]. The presentation illustrated several control room deficiencies found at US NPPs at that time. Also, before the TMI accident training of operators in various accident sequences using full scope simulators was standard practice at many power plants around the world.

In the aftermath of the TMI accident, the first probabilistic safety assessments (PSAs) were developed. The PSA methodology provides means to calculate probability estimates for selected sequences of events that may challenge plant safety. Selecting a set of accident scenarios, their combined impact on the core damage probability can be calculated.

The methodology has been successfully used for technical improvements and preliminary suggestions for extending the methodology to HOF issues were proposed [19].

The presentations and papers at a conference in Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1986 provide an overview of activities initiated by the nuclear domain in response to the TMI accident [20]. Browsing the sessions and papers one can see—among other things—that control room design, operator support systems, and human reliability were addressed. Additionally, organizational issues were presented in two sessions, with papers on communication, training, and human performance as well as work and organizational structure. It is also notable that members of the international nuclear community were well represented at the conference.

The documentary nature of the conference material cannot fully reflect the implementation of lessons learned around the world; however, we can see that at least awareness of the importance of HOF was increasing, taking the first steps.

Comentários

Postar um comentário