Prevent Tragedies - Lessons learned from the Loss of Air France 447 Off the Brazilian Coast and RISK MANAGEMENT modules, AND THE PROACTIVE SAFETY METHOD, RISKS AND EMERGENCIES

Lessons learned from the Loss of Air France 447 Off the Brazilian Coast and ProSREM

Reference: Organizational Accidents Revisited - James Reason

Background

On 1 June 2009, Air France Flight 447 (AF 447) took off from Rio de Janeiro with 228 passengers and crew on board. It was scheduled to arrive at Charles de Gaulle Airport, Paris, after an 11-hour flight, but it never arrived. Three hours later, it was at the bottom of the ocean. There were no survivors. Of all the case studies considered here, I find this one the most horrific, mainly because, unlike most of the others, the victims could be anyone. At three hours into a long-distance flight, it is likely that dinner had been served and that most of the passengers would have been composing themselves for sleep, reading, or watching videos.

The flight crew comprised the captain and two co-pilots. The aircraft was an Airbus 330-200. In line with European Commission Regulations, the captain told the two co-pilots that he was going to the bunk bed, just aft of the flight deck for scheduled rest. Unfortunately, the captain did not give explicit instructions as to who should be the pilot flying (PF). The co-pilot he left with primary controls was the junior and least experienced of the two, though he did have a valid commercial pilot’s license. This omission had serious consequences because the captain should have left clear instructions about task sharing in his absence from the flight deck.

The Event

In the early hours of 1 June 2009, the Airbus 330-200 disappeared in mid-ocean beyond radar coverage and in darkness. It took Air France six hours to concede its loss and for several days there was absolutely no trace, and even when the wreckage was eventually discovered, the tragedy remained perplexing. How could a highly automated state-of-the-art airliner fall out of the sky?

It was five days before debris and the first bodies were recovered. Almost two years later, robot submarines located the aircraft’s flight recorders.

The immediate cause of the crash appeared to be a failure of the plane’s pitot tubes – forward-facing ducts that use airflow to measure airspeed. The most likely explanation was that all three of the pitot probes froze up suddenly in a tropical storm. This freezing was not understood at the time.

The flight crew knew that there were some weather disturbances in their flight path. But because of the limited ability of their onboard weather radar, they didn’t realize that they were flying into a large Atlantic storm. The danger with such storms was that they contained super pure water at very low temperatures. On contact with any foreign surface, it immediately turns to ice. This it did on contact with the pitot probes, overwhelming their heating elements and causing the airspeed measurements to rapidly decrease. This, in turn, caused the autopilot to fail, requiring the pilots to take control of the aircraft manually. The disengagement of the automatic systems created an overload on the Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System and the electronic Centralized Aircraft monitoring messages. The pilots were not equipped to cope with this cascade of failure warnings and control the aircraft. What could have saved them? The by-the-book procedure is to set the throttles to 85 percent thrust and raise the elevators to a five-degree pitch.

Unfortunately, the PF repeatedly made nose-up inputs that exacerbated the failures, putting the aircraft into a stalled condition when there had already been two stall warnings. He did this by pulling back on the stick – unlike a more conventional control column or yoke, the Airbus stick was a short vertical control (located to the right of his seat) that responded to pressure, but did not do so visibly. Without this visual cue, the pilot not flying (PNF) took half a minute or so to figure out what the PF was doing. The PnF said ‘we’re going up, so descend. seconds later, he ordered ‘descend’ again. At this point, the aircraft was in a steep nose-up attitude and fell towards the ocean at 11,000 ft per second. During that time, there were over 70 stall warnings. The PF continued to pull back on the stick and continued to climb at the maximum rate.

Seconds after the emergency began, the captain returned to the flight deck. He sat behind the two co-pilots and scanned the instrument panel, and was as perplexed as his colleagues. There is one final interchange:

02:13:40 (PNF) ‘Climb … climb … climb … climb’ 02:13:40 (PF) ‘But I’ve had the stick back the whole time!’ 02:13:42 (Captain) ‘No. No. No … Don’t climb … No. No’. 02:13:43 (PNF) ‘Descend … Give me the controls … Give me the controls.

02:14:23 (PNF) ‘Damn it, we’re going to crash … This can’t be happening.

02:14:25 (PF) ‘But what’s going on?’

Conclusion

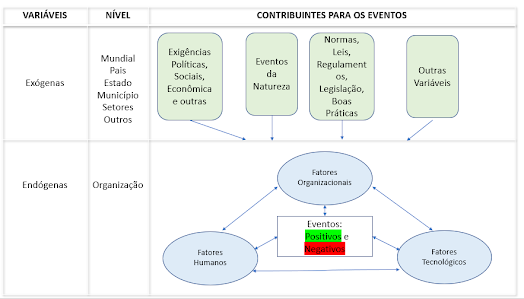

When we study a group of individuals, we recognize the commonalities and note the differences, and in the case of people, it is usually the latter that is regarded as the most interesting and important. But for the case studies outlined above, it is the other way round. We readily appreciate the differences in the domain, people, and circumstances; but what interests us most are the common features, particularly the systems involved and the actions of the participating players.

One obvious feature of these case studies is that they all had bad outcomes. Of more interest, though, is the way that these grisly things happened. It was thoughts like these that set the swiss Cheese model in motion. In my view, all the events had two important similarities: systemic weaknesses and active failures on the part of the people involved. neither one is a unique property of any one domain. The question this chapter addressed was how do these two factors combine to bring about unhappy endings? In most cases, the answers lie in what was happening on the day and in the prior period. These are almost too varied to be sensibly categorized, but that is what this book is about. But, more than that, it is part of an effort to discover and predict the ways that this malevolence combine to achieve their mischief.

Comentários

Postar um comentário