Averting Disaster Before It Strikes - How to Make Sure Your Subordinates Warn You While There is Still Time to Act - Dmitry Chernov · Ali Ayoub · Giovanni Sansavini · Didier Sornette - and RISK MANAGEMENT modules, AND THE PROACTIVE SAFETY METHOD, RISKS AND EMERGENCIES

Dmitry Chernov · Ali Ayoub · Giovanni Sansavini · Didier Sornette

Averting Disaster Before It Strikes

How to Make Sure Your Subordinates Warn You While There is Still Time to Act

With contributions from Washington Barbosa

THE PROBLEM

After a major disaster, when investigators are piecing together the story of what happened, a striking fact often emerges: before disaster struck, some people in the organization involved were aware of dangerous conditions that had the potential to escalate to a critical level. But for a variety of reasons, this crucial information did not reach decision-makers. Therefore, the organization kept moving ever closer to catastrophe, effectively unaware of the possible threats. In the event of an accident, losses and costs for dealing with the consequences are often hundreds — or even thousands — of times greater than the finances that would have been required to deal with the risks when they were first recognized, and before they led to a major accident. Due to the asymmetry of risk information at different levels of the corporate hierarchy of critical infrastructure companies, preventive decisions were not taken in a timely manner. Ultimately, this led to the organizations facing catastrophic events. This observation has been documented in the following major technological accidents: Challenger space shuttle explosion (USA, 1986); Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster (USSR, 1986); Sayano-Shushenskaya hydropower plant accident (Russia, 2009); Deepwater Horizon oil spill (USA, 2010); Fukushima-1 nuclear power plant disaster (Japan, 2011); methane explosions at American and Russian coal mines in the 2010s, and in several other disasters. Detailed information on the importance of this issue for many critical infrastructure companies worldwide is presented in Chapter 1.

WHY THE PROBLEM EXISTS

Chapter 2 takes a detailed look at the reasons why there is a problem with transmission of objective information about safety and technological risks in large critical infrastructure companies.

WHO CREATES AN INTERNAL CLIMATE WITHIN AN ORGANIZATION WHERE IT IS NOT ACCEPTABLE TO TALK ABOUT PROBLEMS?

97% of interviewees (97 out of 100 respondents) answered that most of the blame lies with managers. 2% of respondents argued that the responsibility is equally shared by managers and subordinates. 1% of respondents believed that the reasons for such an internal corporate atmosphere lay mostly in the personal qualities of individuals and their relationship with colleagues, and not in their organizational roles, whether manager or subordinate. None of the respondents placed the main responsibility on employees.

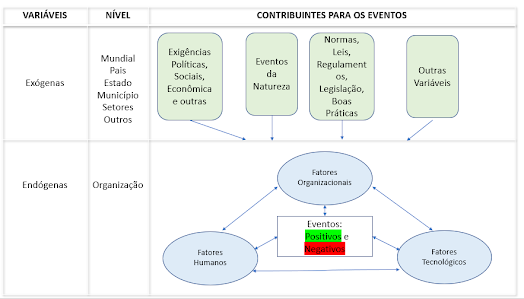

Note from Washington Barbosa: it is important to verify that in major accidents, the exogenous variables influence the endogenous ones, the actions of managers and the direction, more in the links at the end of this post about the Center for Studies and Course on Risk Management and Prevention of Tragedies (Major, Fatal and Serious Accidents ).

TOP 10 REASONS WHY LEADERS DO NOT WANT TO HEAR ABOUT PROBLEMS FROM THEIR SUBORDINATES

1. Tackling reported problems will be costly, and owners and shareholders are imposing strict financial and production targets (58%: 58 out of 100 respondents). Senior managers do not want to hear about problems from their subordinates because the costs of addressing any serious issue in a critical infras-tructure company will be very high. In addition, owners and shareholders are often imposing strict financial and production targets on their senior managers already. Reports from employees about any serious safety and technological problem may threaten the implementation of these plans, as well as negatively affecting the career and the earnings of senior managers.

2. Managers are afraid of being seen as incompetent if they take responsibility for previous bad decisions that have created current problems (38%). When employees inform managers about any serious problem and risk, they are indi-rectly hinting towards the bad decisions and mistakes made by managers in the past that have led to the problem developing in the first place. Rather than admitting that they may have made a mistake, managers try not to hear about or respond to current problems.

3. Senior management assume that once they have been told about a problem, they will need to solve it (36%). Managers are afraid that, if an employee informs them about a problem, the responsibility to solve it is automatically transferred on their shoulders.

4. Senior managers expect employees to solve problems independently in their area of responsibility (28%). Some managers prefer not to pay attention to warnings from employees, because they believe that employees are paid well enough and should be able to deal with problems that arise independently, without involving them.

5. Senior management prefer not to know about risks, in order to avoid being held responsible (including legal responsibility) if things go wrong (27%). Some managers do not want to hear about existing risks from their employees because they do not want to be held legally responsible for an accident or emer-gency. Irrationally but perhaps understandably, they believe that, if risk infor-mation does not reach management, the responsibility for the onset of an emer-gency remains entirely with their subordinates who are managing the facility involved. This has some basis in experience. During investigations following major accidents in critical industries worldwide, some senior executives were able to avoid criminal liability because they claimed they had not been aware of the problems that ultimately led to the accidents — while their subordinates, unable to plead ignorance, were punished.

6. Leaders do not want to step out of their comfort zone to solve complex questions (26%). Some leaders do not want to step out of their comfort zone, change their routine, and take on extra work to react to problems their employees have warned them about. This may as well sometimes imply that managers have to rush to a production site in a remote region to deal with the problem on the spot.

7. Leaders are people too — like anyone, they would rather hear good news than bad ones (24%). One should remember that leaders are just humans underneath, and it is just human nature to prefer good news rather than bad.

8. Managers see issues reported by employees as unimportant (23%). From the perspective of some managers, most of the problems employees bring to senior management are insignificant. As a result, some executives are reluctant to hear about the concerns of rank-and-file employees and do not want to have to respond, as for them these are minor issues. But with this approach, there is the chance that vital information about critical risks may be overlooked.

9. Short-term contracts for managers (19%). The reluctance of some managers to hear about serious problems is influenced by their own short-term contracts, as part of a company’s short-term corporate goals. The short-term contracts of senior managers (up to 3 years) are detrimental to creating a favorable environ-ment for the reporting of information about risks. Leaders feel under pressure to show shareholders a quick positive result, therefore they are unwilling to receive bad news about production issues that will require time and money to rectify. Solving serious problems in critical infrastructure companies generally requires sustained effort over many years.

10. A common corporate leadership culture pervades the entire company and industry (15%). In some large companies, a corporate culture of “no bad news” accumulates over decades. Entire generations of leaders have grown up in a culture in which only good news can be brought to the authorities.

HOW THE PROBLEM CAN BE SOLVED

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR OWNERS AND SENIOR MANAGEMENT: TEN PRACTICAL WAYS TO IMPROVE THE QUALITY AND SPEED OF RISK INFORMATION TRANSMISSION WITHIN CRITICAL INFRAS-TRUCTURE ORGANIZATIONS

The handbook draws on information received from 100 practitioners in industry, and the results of a decade of research on the reasons for concealing risks before and after major technological accidents. Together they inform some clear practical recommendations for owners and managers of large industrial companies, who want to fundamentally improve the transmission of risk information within their organi-zation, in order to prevent serious industrial accidents. A detailed account of the recommendations is presented in Chapter 3.

1. Owners and senior management should be willing to give up short-term profits in exchange for the long-term stability of critical infrastructure.

Fundamental improvements in the quality and speed of reporting critical risks within a critical infrastructure company are possible only when the owners and senior management are willing to focus on the long-term ownership of the company. This involves accepting that the significant costs required to manage existing serious and critical risks may impact short-term profits, but are essential to protect the long-term reliability, sustainability, and value of the company. The owners will make more money on the long-run and with much less risk in case of investing in reliability of critical infrastructure, which increases the long-term return and decreases the short-term risks and volatility. If owners are willing to allocate resources to prevent critical problems, then their managers will follow suit and begin to pay attention to these safety issues. The changed view regarding safety in the minds of senior management will lead over time to a change in attitudes and working practices throughout the company. To operate sustainably in the long term, a critical infrastructure company must find a balance between safety, finance, and production. The task of top management is to create a system that allows managers at every level to freely analyze and discuss risks and to find the acceptable balance.

2. Senior management should be approachable about problems, and have the desire and resources to control and mitigate identified risks.

Everything comes from leadership. Employees will report problems if managers want to hear them. Managers should want as much information as possible about poten-tial risks. If the management support is not there, all other interventions are doomed to fail. The only way to improve the situation regarding feedback in an organization is if leaders have a genuine desire to hear about risks from their subordinates — and communicate this to them — and then take decisions and allocate resources to stop risk escalation. Senior managers should have the necessary support — moral and practical — from owners and shareholders to implement risk reduction measures. Having secured this, they should then take the initiative to implement cultural change, dismantling any system of penalties for reporting risks or incidents, and making it clear that they actively want to hear about problems. Only then will employees, inspired by the evident commit-ment of their leaders to a safer workplace, be willing to report the risks they have encountered.

3. Risks must be prioritized, as it is impossible to manage every risk within an organization simultaneously.

It is impossible to effectively manage all risks — prioritization is essential. Resources are always limited and will never be sufficient to mitigate every possible risk. Without establishing clear priorities, managers have so much information to handle that they cannot distinguish what is important from what is not. A gradation of risks immediately makes the situation clearer — what further information is required, which risks need monitoring, and which demand urgent action so that “major negative events” can be prevented. It is vital that critical risks and problems that may threaten the work of an entire enterprise come swiftly to the attention of senior managers so that they can immediately inform the highest level of the hierarchy, while less serious risks can be delegated to appropriate lower levels of management for further action. For effective decision-making, you need to have a system in place to deliver an integrated risk assessment of production processes, where all the key risks of an industrial facility are assessed and then ranked by severity. This will enable an organization to prioritize the allocation of risk management resources. Not all employees in the organization are dealing with critical risks — only a limited circle of managers and employees is responsible for this. Senior managers should start by working on the control and reduction of critical risks with those managers and employees who manage them.

4. Senior managers must be leaders in safety.

It is imperative that any initia-tive to prioritize safe operation of critical infrastructure comes from senior management. In highly hierarchical companies, the example set by the leader is paramount. Most critical infrastructure companies have several management levels and are quite bureaucratic. If subordinates see that safety is extremely important to the CEO, and the entire corporate system makes it a top priority, then most employees will imitate senior management and follow the principles they are espousing. If safety is made the top priority by the CEO, then production site workers have no grounds for relegating it down the list of their own priorities, and will instead be willing to place it first, above production and profitability indicators.

5. Senior management should build an atmosphere of trust and security, so that employees feel safe to disclose risk-related information.

Without trust in the leadership, there can be no high-quality feedback from employees on the problems of an organization. Often, employees evaluate the possible consequences of disclosing risk information based on rumors about how senior management reacted in a previous situation with colleagues. Employees project both the positive and negative experiences of their colleagues onto themselves. Employees need to have security guarantees, both for their careers and for their colleagues. Managers must guarantee the security of their sources and take responsibility for solving any significant problem they are informed about. If an environment can be established where employees do not feel under threat, they will begin to give candid feedback. To increase employee confidence, it is essential to reduce their uncertainty about the actions of managers. Managers need to demonstrate exactly how employees are treated when they give honest feedback. Only through repeated positive responses from managers will it be possible to dispel the common perception that an organization can be dangerous to employees who speak out. The first step is for senior management to make a declaration that feedback is encouraged at all levels of a company. Nevertheless, this is not enough in itself: employees must see the truth of the statement applied in practice, with employees receiving praise and not punishment for offering honest feedback. The message that senior management actively want to hear about problems, and that it is safe for employees to tell them, should come right from the top of the hierarchy. It is important that the CEO and senior executives give employees specific examples of their colleagues’ positive experiences of communicating problems to their seniors. It is also vital that managers demonstrate respect for their subordinates, including a sincere interest in their well-being, safety, and progress. If these principles are applied reliably across the board, then even the most cautious employees will gradually come round to the idea that a company is a safe environment, where they can confidently reveal their concerns about the situation on the ground without any negative consequences.

6. Middle management are allies of senior management in building an organization where active dialogue between superiors and subordinates is welcomed.

Senior management can only build an effective system to obtain accurate information about risks, and change the safety culture in a company, by working with the middle managerial level. Therefore, the best strategy is to make middle managers allies and not enemies. The middle managers in charge of the production facilities know more about the situation at an organization than shop floor employees and lower-level managers. If senior managers only ask for the opinion of shop floor employees about the critical risks of an organization, they may not always get an accurate assessment of the situation. Getting information about critical risks only from lower-level employees may just lead to an increase in information noise, making it more difficult for senior management to understand the true picture of safety at a site. Once honest dialogue has been established between senior management and owners about critical risks and how to handle them, the next step is to establish the same honest dialogue between the leadership and the middle management level. Senior management should emphasize that they trust middle management. They must ensure that middle managers disclosing risks and problems are not penalized or dismissed. They must show that they want to work together with middle managers to solve problems, and not leave them to tackle issues alone. They must appreciate and reward subordinates who provide accurate information. It is also important that middle managers have the opportunity to adjust the production plans set by headquarters, so that they have the authority to stop suspicious pieces of asset for repair and the resources to carry out these repairs.

7. Use different upward risk transmission channels.

In addition to receiving information through the traditional management hierarchy, senior managers are encouraged to regularly visit industrial sites to hear directly from managers and employees regarding the critical risks they are facing. It is also recommended to use other alternative channels for obtaining information about risks, such as: fault logs or risk registers/databases; safety training observation program cards; smartphone apps to allow shop floor employees or lower-level managers to timely report risks to senior managers directly; independent production monitoring systems; process improvement proposals; problem-solving boards; and anonymous mailboxes and helplines.

8. The words of leaders should be supported by their actions: problems once identified need to be solved.

Leaders should never say one thing and then do another — their words must be matched by their deeds. This is especially relevant if senior managers call for risk disclosure, and then consistently address the issues that their subordinates bring to their attention. When employees report risks and problems, they do so in the belief that managers will make the right decisions to solve the problem or at least reduce the risk. A critical infrastructure company may well not have enough resources to solve all the problems identified at any given time. If this is the case, then managers must be sure to feed back to the employee who reported an issue, and assure them that they will tackle the problem when they can. If identified problems are not satisfactorily solved, then employees will inevitably lose faith, and will not bother to disclose risks to their superiors anymore.

9. Do not penalize specific employees: look for systemic defects within the organization.

Executives should not penalize individual employees for incidents, but instead look for the systemic shortcomings in a company’s operations that forced the employees to commit safety breaches.

10. Reward employees for disclosure of safety and technological risks.

The best way to reward employees is to recognize their important contribution to an organization, as everyone derives fulfillment from having their work appreciated and praised. Management should deliver this not just through a private conversation, but in front of the whole workforce. Expressing gratitude publicly in this fashion provides an opportunity for senior management to highlight the kind of behavior and performance they wish to see from all their employees. Public recognition will motivate the employee to even greater efforts and encourage colleagues to communicate new risks and problems up through the hierarchy. According to most respondents, non-financial motivation is more effective than material incentives, which have many disadvantages. There are many effective ways to motivate employees for disclosing information about risks, which do not involve financial reward.

Book Link Averting Disaster Before It Strikes:

For more information, videos, and complementary materials, about Safety, access the links at the end of this post.

Are we paying attention to the essential issues for the Safety of Organizations?

How many lives, what social, environmental, patrimonial impact, in the image of the organization and others, would be spared?

It is important to look into these issues, and to deepen academic studies, with application in companies, to develop proposals to avoid these tragedies.

Below is the proposal for preventing and mitigating major and fatal negative events, which I developed based on studies and applications in organizations.

It is important to present models, principles and structured forms, together with lessons learned from Major and Fatal Negative Events, which facilitate the analysis of these tragedies, That's why I created the Prevent Tragedy Course - Proactive Safety, Risks, and Emergencies Methodology (ProSREM).

I developed ProSREM, in my Ph.D., in Production Engineering at UFRJ, and used as academic bases: Ergonomics, Resilience Engineering, Integrated Management Systems (Quality, Safety, and Environment), among other methods and tools, and my database to build this proposal, was the biggest and fatal negative events, prominent in the world and in Brazil, I apply this methodology at Fiocruz, where I am a public servant and in organizations, companies, sectors, and activities.

If you are interested in the proposal, send me an email, and when there is the availability of e-learning training, of the Introductory Course of the Proactive Safety Method, Risks and Emergencies, I can contact you, the email is:

washington.fiocruz@gmail.com

I will send you a form, for your registration, for the e-learning training.

If you are a professional with experience in the area of safety, risk management, or similar areas, the initial training will consist of two 1-hour meetings, plus guided reading of the modules, complementary materials, and other guidelines, which I will send.

I will assemble these training, in order of registration, so speed up yours, to start the course earlier.

This course will be free of charge and will help me at this stage of my research, for the Doctorate in Production Engineering at UFRJ.

Prevent Tragedy Course - Reports of professionals from the course's study cycle:

- They liked the proposal, it lacks this approach with application in the industry (deficiency in the training), very didactic, motivating for the theme, bringing reality, bringing disasters, it could be avoided, ANDEST (National Association of Teachers in Engineering Safety at Work in Brazil) identified a deficiency in risk management in the training of the safety eng., posts of proactive safety are important, you raise the ball, it is up to people to absorb the lessons of the post, I encourage them to understand what happened, think about all the aspects, awaken this need for analysis.

RISK MANAGEMENT modules, AND THE PROACTIVE SAFETY METHOD, RISKS AND EMERGENCIES.

Module 1, UNDERSTANDING AND PREVENTING TRAGEDY:

Module 2, THEORY OF THESE TRAGEDY - SHORT VERSION:

Module 3, CASE STUDIES OF THESE TRAGEDY:

Module 4, EXERCISES AND ACTIVITIES, TO UNDERSTAND AND PREVENT TRAGEDY:

Article approved in JRACR journal - The Sociotechnical Construction of Risks, and Principles of the Proactive Approach to Safety

Participate, specialize and support the dissemination of this initiative.

Washington Barbosa

.jpg)

Comentários

Postar um comentário