Railway Accident in Amagasaki (April 25, 2005) An Enhanced Analysis through Proactive Safety Engineering

Railway Accident in Amagasaki (April 25, 2005)

An Enhanced Analysis through Proactive Safety Engineering

Based on the Models of Washington Ramos Barbosa

Abstract

The railway accident in Amagasaki, Japan, which resulted in 107 fatalities and hundreds of injuries, has often been explained in a limited manner by operational error and excessive speed. This article deepens the analysis by applying the Proactive Safety Engineering framework developed by Washington Ramos Barbosa, integrating three complementary models: the Proactive Safety Approach, Dynamic Risk Management, and the Systemic Vision of Safety integrated with other organizational areas. The study demonstrates that the accident was not the result of an isolated human failure, but rather the consequence of a progressive degradation of safety margins of organizational, cultural, and systemic nature. By reinterpreting the event through these models, the article contributes to a deeper understanding of the prevention of major accidents in complex sociotechnical systems.

1. Introduction

Major railway accidents continue to occur even in highly regulated and technologically advanced systems. Traditional safety analyses tend to focus on immediate technical failures or individual violations, limiting organizational learning and reinforcing reactive safety practices. Proactive Safety Engineering, as formulated by Washington Ramos Barbosa, proposes an alternative paradigm by emphasizing anticipation, organizational learning, and systemic integration of safety into management processes.

This article applies Barbosa’s three interrelated models to the Amagasaki derailment, demonstrating how organizational pressures, punitive management practices, and weak integration between safety and other organizational functions collectively shaped the conditions for the tragedy.

2. Proactive Safety Approach

2.1 Conceptual Foundations

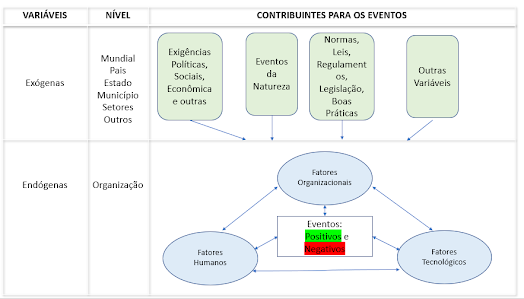

According to the Proactive Safety Approach, accidents are emergent phenomena arising from sociotechnical systems subjected to continuous pressure. Human error is not a root cause, but a visible symptom of deeper organizational and systemic conditions. Safety failures occur when organizations prioritize performance, efficiency, or punctuality without maintaining equivalent investments in safety margins and learning mechanisms.

This approach shifts the analytical focus from individual blame to the context in which decisions are made, highlighting how goals, incentives, norms, and culture influence behavior at the operational level.

2.2 Application to the Amagasaki Accident

In the Amagasaki case, excessive speed is frequently identified as the immediate cause of derailment. However, the Proactive Safety Approach reveals that the driver’s behavior was shaped by a punitive organizational environment characterized by strict discipline for delays, mandatory retraining perceived as punishment, and reputational consequences.

Under these conditions, the driver’s decision to accelerate cannot be interpreted as reckless individual behavior, but as an adaptive response to organizational pressure. The organization implicitly signaled that punctuality was more valued than conservative safety margins. This value conflict drove the migration of operational behavior toward risk.

From a proactive perspective, the organization failed to recognize and manage the erosion of safety culture caused by fear-based management. The absence of psychological safety discouraged transparent reporting and organizational learning, reinforcing unsafe adaptations.

2.3 Contributions of Proactive Safety

The application of the Proactive Safety Approach highlights the need to replace punitive control systems with learning-oriented safety management models, to recognize behavioral adaptations as indicators of system stress, and to treat cultural signals and management practices as leading indicators of major accident risk.

3. Dynamic Risk Management

3.1 Conceptual Foundations

Dynamic Risk Management, within the context of Proactive Safety Engineering, recognizes that risk is not static. Risk levels fluctuate continuously due to workload, performance pressure, operational variability, and organizational decisions. Accidents occur when risk progressively migrates beyond acceptable limits without detection or intervention.

This model emphasizes the identification of weak signals and early warnings that precede major accidents.

3.2 Risk Migration in the Amagasaki Accident

The Amagasaki accident clearly illustrates a trajectory of risk migration. Normal operations were characterized by rigid schedules and minimal tolerance for deviation. Recurrent delays and accumulated penalties generated chronic stress. Operators adapted by compensating time through increased speed. Safety margins were gradually eroded until the system crossed a critical threshold.

Dynamic Risk Management failed because the organization lacked mechanisms to detect and respond to these signals. Disciplinary records, communication patterns, and near-miss behaviors were treated as compliance issues rather than indicators of rising systemic risk.

3.3 Missing Dynamic Interventions

From Barbosa’s perspective, effective dynamic risk management would have included continuous monitoring of organizational pressure indicators, not only technical parameters; intervention protocols triggered by patterns of stress and adaptation rather than solely by rule violations; and flexibility in operational schedules to safely absorb variability.

The absence of these mechanisms allowed risk to accumulate silently until its catastrophic release.

4. Systemic Vision of Safety Integrated with Other Organizational Areas

4.1 Conceptual Foundations

The Systemic Vision of Safety proposed by Washington Ramos Barbosa asserts that safety cannot be confined to a technical or operational function. Safety is a property of the entire organization and must be integrated with production, logistics, human resources, finance, maintenance, and emergency response.

Failures occur when safety objectives are isolated while other organizational areas pursue conflicting goals.

4.2 Organizational Integration Failures in Amagasaki

Production and Logistics

Punctuality targets were established without sufficient coordination with safety constraints imposed by infrastructure geometry. The organization failed to reconcile performance goals with physical limits.

Human Resources

Disciplinary and retraining policies prioritized correction through punishment, reducing transparency, increasing fear, and discouraging organizational learning.

Finance and Investment

Investment decisions did not adequately prioritize advanced automatic speed control and protection systems capable of compensating for predictable human and organizational variability.

Maintenance and Technology

Safety-critical technologies were not deployed as systemic barriers against foreseeable human adaptations under pressure.

Emergency Response

Post-accident analyses indicated difficulties in command, control, and communication during rescue operations, demonstrating that systemic safety integration must also encompass the response and resilience phases.

4.3 Systemic Value Creation

A systemic vision reframes safety as an organizational strategy. When aligned across functions, safety strengthens reliability, reputation, sustainability, and long-term performance.

5. Integrative Discussion

The Amagasaki accident exemplifies how major disasters emerge from the interaction of cultural, organizational, and technical factors. The three models of Proactive Safety Engineering do not operate independently, but synergistically.

The Proactive Safety Approach explains why unsafe behaviors emerge.

Dynamic Risk Management explains how risk migrates over time.

The Systemic Vision of Safety explains why organizations fail to interrupt this migration.

Together, these models offer a comprehensive framework for preventing major accidents in complex systems.

6. Conclusion

The enhanced analysis demonstrates that the Amagasaki railway accident was not an inevitable consequence of individual human error, but the result of systemic failures in managing organizational pressure, dynamic risk, and cross-functional integration. Washington Ramos Barbosa’s Proactive Safety Engineering provides a robust theoretical and practical framework for understanding and preventing major accidents by repositioning safety as a proactive, strategic, and systemic organizational capability.

---

Comentários

Postar um comentário